Module 2

A History of Oil & Gas Discoveries in the Gulf

Introduction

This module focuses on a sociopolitical history of the oil and gas industry in the Gulf region. It will first explore oil discoveries in the Gulf states. Then it will focus on the historical development of the oil & gas industry in Qatar including Qatar’s involvement in Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF). In the final section, we will examine a brief labor history of the oil and gas industry in Qatar by identifying the common themes lived through by some of the early workers in the industry.

Oil Discoveries in the Gulf

Persia

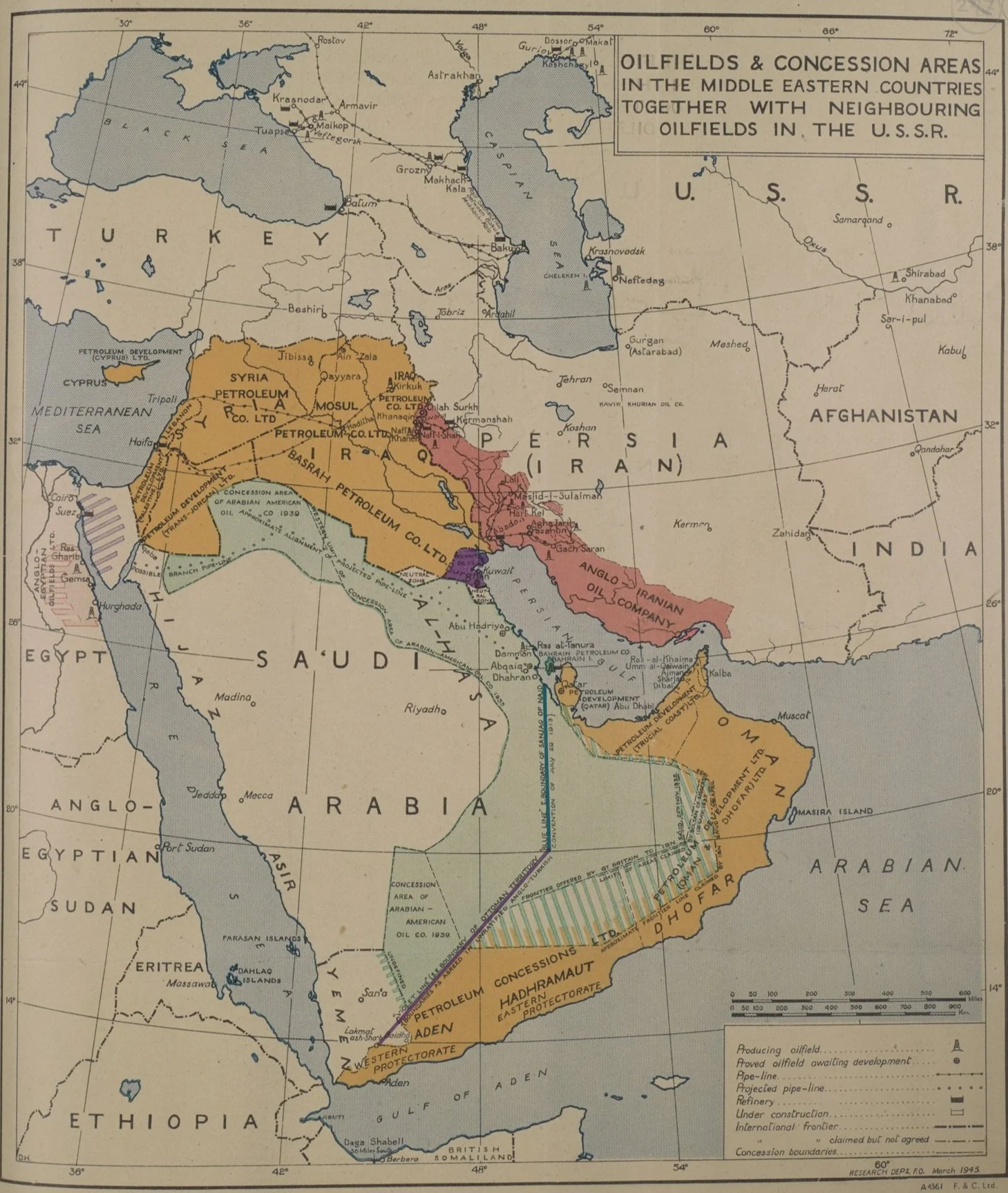

Figure 1. This map of the Middle East was produced in March 1945 by the Research Department of the Foreign Office. (British Library, IOR/R/15/1/700, f 248)

Oil in the Gulf and in the Middle East was first found at the start of the 20th Century. English entrepreneur William Knox D’Arcy was awarded a concession by the Persian Government (in modern-day Iran) in 1901 to search for oil in Ghasr-e-Shirin and Chiah Surkh (Smil, 2008). This search for oil took seven years before a significant amount was finally found in Masjid Sulaiman on May 26, 1908, in the southwest corner of Persia, located close to the border of Turkish Mesopotamia –– current day Iraq (Hobbs, n.d., Smil, 2008 & Yergin, 1991). A year later in 1909, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), the precursor of modern-day British Petroleum (BP) was created (Smil, 2008). After hearing Britain’s plans to convert its naval fleet from running on coal to oil, APOC’s prospectus to investors was to sell oil found in Persia for marine purposes, especially for warships (Hobbs, n.d., Smil, 2008 & Yergin, 1991, pp. 11-12).

Figure 2. A map that accompanied APOC’s prospectus to investors. (Stanford’s Geographical Establishment, British Library, IOR/L/PS/10/144/2, f 216)

The discovery and exploitation of oil in Persia by Britain was the start of a long history of foreign involvement in the region’s oil and gas industry. Several oil concessions would later be given to foreign companies around the region: Iraq in 1927, Bahrain in 1925, Qatar in 1935, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in 1938, the United Arab Emirates in 1958, and Oman in 1964. This module will provide a brief overview of oil discoveries and development in the region before detailing similar endeavors in Qatar.

Iraq

Modern-day Iraq, once known as Mesopotamia, plays a large role in the Middle Eastern oil industry.

Attention was drawn to Mesopotamia’s oil when the Masjid Sulaiman field in Iran was discovered by APOC in 1908 (Sorkhabi, 2009). APOC petroleum engineer and geologist, George Bernard Reynolds drilled the first wells in Chiah Surkh between 1902-1903 (Sorkhabi, 2009). Though the region was not part of modern-day Iraq at the time, it would be transferred to the Ottoman Empire in 1913. Although the Chiah Surkh wells produced oil and gas, the wells were abandoned for more productive prospects until APOC revisited the area –– specifically, Naft Khaneh –– in 1909 (Sorkhabi, 2009). The field was further developed in 1925 by the Khanaqin Oil Company –– a subsidiary of APOC –– who would later build the first oil refinery and pipeline in Iraq in 1927 (Sorkhabi, 2009).

Figure 3. Illustration by Rasoul Sorkhabi (modified from R.J. Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology, volume 1, Leiden, 1955)

An Armenian engineer, businessman and Ottoman Empire citizen, Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian kept a close eye on the prospect of oil in Mesopotamia. Well-educated in petroleum engineering at King’s College in London and with experience from his father’s oil industry in Baku, the Ottoman empire asked Gulbenkian to investigate oil in Mesopotamia in 1891 (Sorkhabi, 2009 & Yergin, 1991). Mesopotamian oil would be Gulbenkian’s focus for the next few decades.

In the early 20th century, Western businessmen and diplomats from Germany, France, Britain (represented by APOC), and the United States were keen to obtain a stake in oil prospects in the area. Informal arrangements began after a promising geological report of Iraq was acquired by a German survey team in 1905 (Sorkhabi, 2009).

More formal arrangements were made in 1912 when German-born English banker with notable influence in Istanbul, Sir Ernst Casel, registered the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC) in London (Sorkhabi, 2009). Shortly after, an informal oil concession was obtained from the Turkish government by Gulbenkian who was involved in British ventures in Turkey all along and was granted British citizenship in 1902 (Sorkhabi, 2009). In 1914, after requests from British and German ambassadors, permission was granted to TPC to explore oil in Mosul and Baghdad by Turkey’s Grand Vizir, Said Halim (Sorkahbi, 2009). A new TPC was formed in 1914 with British interests (Turkish National Bank and D’Arcy Group, an APOC subsidiary) holding 50%, German interests (through Deutsche Bank) holding 25%, and Royal Dutch-Shell holding 25%. However, 2.5% of each Royal Dutch-Shell and D’Arcy Group’s shares were given to Gulbenkian (Sorkhabi, 2009).

The TPC, however, only remained a company on paper up until this point. World War I halted any further development of TPC. After the war the Ottoman Empire was broken into several regions. Mesopotamia became a British mandate and adopted the name we know today, Iraq. In 1921, the British installed Faisal, who had fought against the Ottoman Turks during the war, as Sultan in Iraq (Sorkhabi, 2009).

Two major geological expeditions took place in Iraq around the same time. Edwin Pascoe of the Geological Survey of India led the first expedition between 1918-19 and the second, Arthur Nobel and Ralph Evans of Shell led between 1919-20 (Sorkhabi, 2009). During this time, Germany’s shares were in question because of its defeat in WWI. British and French officials concluded that these shares should be handed to France (Sorkhabi, 2009). Unhappy, the United States pressured Britain to allow American companies to enter the region, a desire that Britain would later support because of the benefits of America’s funding, technology and political support (Sorkhabi, 2009). Meanwhile, Walter Teagle, president of the New Jersey Standard Oil Company, was in constant contact with TPC officials (Sorkhabi, 2009).

TPC finally obtained a formal concession on March 24, 1925 from the Iraqi government (Sorkhabi, 2009). A massive geological expedition shortly commenced with experts from the United States, Britain, and France. Based on their findings, TPC drilled four wells in Kirkuk and two in Palkhana in 1927 (Sorkhabi, 2009). Of all these sites, Baba Gurgur No. 1, a well in Kirkuk, became Iraq’s first oil gusher (Sorkhabi, 2009).

On July 31, 1928, TPC instituted a new ownership structure. APOC would now hold 23.75%; Royal Dutch-Shell, 23.75%; Compagnie Francaise des Petroles, 23.75%; Near East Development Corporation (a group of American oil companies: Jersey Standard, Socony, Gulf Oil, Pan-American and Arco), 23.75%; and finally, 5% for Mr. Gulbenkian (Sorkhabi, 2009). In the same meeting these terms were decided, Gulbenkian took a red pen and drew a line around the boundaries once held by the Ottoman Empire and required all signatory companies to work together or not at all in exploring any of the areas within the Red Line (Sorkhabi, 2009 & Yergin, 1991). This would be popularly known as the Red Line Agreement. This agreement was the source of much contention from American companies that would enter other Gulf countries soon after. In the late 1940s, as British influence in the region weakened and America’s international influence (and corporations’ power) grew, the Red Line Agreement would disintegrate (Yergin, 1991 & U.S. Office of the Historian, n.d.)

Figure 4. Map showing the extent of the Red Line Agreement, 1928 (Morton [GeoExpro], 2013, June)

The Kirkuk discovery in 1927 was a turning point in Iraqi history and the birth of the Middle Eastern oil industry (Sorkhabi, 2009). In 1929, TPC officially changed its name to Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC). In 1930, Iraq gained independence from Britain, then signed a new agreement with IPC in 1931 to require royalties of four shillings per metric ton of oil produced, plus a minimum annual payment of £400,000 for the first twenty years (Sorkhabi, 2009). These terms and agreements would be the basis and inspiration for Gulf leaders who found themselves negotiating similar terms in their respective nations.

Oil production from the Kirkuk field began in 1934 and is considered Iraq’s largest oil field today. IPC would continue to develop as activities began in Mosul and Basra (creating the Mosul Petroleum Company and the Basrah Petroleum Company) which kickstarted Iraq’s petroleum industry (Sorkhabi, 2009). These companies were finally nationalized in 1973 (Sorkhabi, 2009).

Bahrain

Bahrain’s location is central to the trading routes between Iraq and the Indus Valley, making it invaluable to the Omani copper trade around 4,000 years ago (Archer, 2012). After the decline of the copper trade, Bahrain became a thriving center of the pearling industry, which became a staple to the nation’s economy until the 19th century (Archer, 2012). Due to its location, Bahrain once again became the trading center of the Gulf, this time to British powers that occupied the region and established the nation as a British protectorate. The Kingdom of Bahrain, once a key player in various industries in the region, would reestablish influence with the discovery of oil.

An important figure in the oil history of the Middle East, Major Frank Holmes played a huge role in developing the industry in Bahrain (and the wider region). Holmes, originally from New Zealand, had a resumé full of international experience as a mining engineer in South Africa, Australia, Malaya, Mexico, Uruguay, Russia and Nigeria (Yergin, 1991). In 1918, during World War I, Holmes was a quartermaster in the British Army and heard about oil in the region while on an expedition to buy beef in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (Yergin, 1991). After hearing of oil seepages in and around the Gulf, he was convinced of an impending oil discovery in Bahrain (Archer, 2012 & Yergin, 1991). Holmes conducted his work in the region through his London-based company, Eastern and General Syndicate. While despised by British officials in the region and London because of his undermining of British influence in the region, Holmes was loved and respected by the local leaders and people –– garnering the nickname, “Abu al-Naft,” or, the “Father of Oil” (Yergin, 1991).

Holmes’ belief that the Gulf region contained major petroleum reserves was met with skepticism by Dr George Lees, an APOC geologist, who promised to “drink every drop of oil produced south of Basra [in Iraq].” No records were found to indicate whether he kept his promise after he was proven wrong (Archer, 2012).

Initially, Bahrain’s ruler, Sheikh Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa, was not interested in oil. Instead he wanted fresh water, which was in short supply (Yergin, 1991). Holmes agreed to search for fresh water. After painstakingly mapping out the entire country and drilling many wells, Holmes found water and consequently was awarded an oil concession in 1925 (Archer, 2012 & Yergin, 1991).

Depleted of resources to fund oil explorations in Bahrain, Holmes sought support from international oil companies. The APOC rejected him, convinced oil would not be found after their geologists’ exploration (Yergin, 1991). Desperate, Holmes travelled to the United States, hoping for more options. Standard Oil of New Jersey rejected his proposal but the Bahrain oil concession came to the attention of Standard Oil of California (Socal) and in 1929, Socal established the BAPCO –– the Bahrain Petroleum Company (Archer, 2012).

However, BAPCO was strongly opposed by the British government because a “British nationality clause” was necessary in any concession agreement to ensure “British interests” in any oil development (Yergin, 1991). A series of negotiations were carried out between the British government and American companies, backed by the United States government. In 1929, Britain finally backed down. Britain released Bahrain and made a deal with Socal, allowing the American company to operate in Bahrain. The condition was that Britain would maintain its political influence in Bahrain, i.e., all of the company’s requirements would go through the British political agent in the country (Yergin, 1991).

Socal finally commenced drilling in Bahrain on October 19, 1931 (Archer, 2012). Soon after –– in 1932 –– the first oil discovery was made in Well Number 1, located near Jebel Dukhan, Bahrain’s highest point at 134 meters above sea level (Archer, 2012). By 1934, Bahrain began exporting oil and Bahrain’s oil industry was well underway (Archer, 2012).

In 1936, the first oil refinery was opened and oil production increased exponentially. Only two years after the Bahrain Petroleum Company refinery was established, the first fueling station opened in Manama, Bahrain’s capital, beginning the nation’s development (Archer, 2012).

While local frustration of British control grew after World War II, BAPCO continued to make important developments. Natural gas was detected in 1948, followed by the discovery of the offshore Abu Safah field in 1963 –– which would prove to be a core income generator for the Bahraini oil industry (Archer, 2012).

In 1968, the British government finally ended treaty relationships with Gulf states that had lasted over a century. Bahrain remained a British protectorate for a few more years before finally declaring independence on August 15, 1971 (Archer, 2012). This began the start of the trend of nationalization in the region (nationalization was also called “participation” in those times as the Gulf countries wanted to increase their participation in the foreign oil companies).

Only five years later, the Bahraini government bought shares from Socal and Texaco to control a 60% stake in BAPCO (Archer, 2012). Soon after, the Bahrain National Oil Company (BANOCO) was integrated and by 1980, the Bahraini government attained 100% ownership of BAPCO (Archer, 2012). The rest of the twentieth century was prosperous for the oil industry in Bahrain, with high levels of production and the establishment of several additional companies like a petroleum marketing business and a gas liquefaction plant (Archer, 2012). BAPCO has continued to invest in strategies to secure the country’s economic future with developments like low sulphur diesel projects (Archer, 2012).

² Socal was one of the companies created after the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911.

Saudi Arabia

In 1932, after years of conquests and wars, Ibn Saud successfully unified the country we know as Saudi Arabia with Riyadh as its capital. The new kingdom faced financial issues; revenue from Muslim pilgrims decreased significantly when the effects of the Great Depression hit other countries (Sorkhabi, 2008 & Yergin, 1991).

Harry St. John Bridger “Jack” Philby played a crucial role in obtaining oil concessions in Saudi Arabia. He worked for the British Indian Civil Service and the British political mission in Baghdad and Basra during World War I. Philby, upset by British policy in the Middle East, quit the Indian Civil Service in 1925 and went to Saudi Arabia to start a trading company (Yergin, 1991). During this venture, he earned the trust and friendship of Ibn Saud who appointed Philby as one of his closest advisors (Yergin, 1991).

During a car ride in the autumn of 1930, aware of his friend’s financial woes, Philby convinced Ibn Saud that Saudi Arabia held great wealth under its territory (Yergin, 1991). Extracting this wealth, however, would require foreign capital and foreign expertise in exchange for money –– all to the King’s benefit. The King, however, was more interested in water than oil (Yergin, 1991). Philby recommended Charles Crane, an American irrigation expert and philanthropist who had ongoing projects in Yemen and Egypt, to be invited to Saudi Arabia (Yergin, 1991).

On February 25, 1931, Crane arrived in Jeddah. The King lavished Crane with all kinds of gifts –– ranging from horses to rugs and daggers (Yergin, 1991). After their newly formed friendship, Crane agreed to finance and send an American mining engineer named Karl Twitchell to prospect for water in the kingdom (Sorkhabi, 2008 & Yergin, 1991).

Around the same time, Francis Loomis, a former U.S. diplomat and Socal’s advisor on foreign relations, sought help from Philby to obtain an oil concession in Saudi Arabia (Sorkhabi, 2008). Soon after Loomis met Twitchell at a lunch party, Socal hired Twitchell as an advisor and sent him and Socal’s lawyer, Lloyd Hamilton to the Kingdom, where they would arrive on February 20, 1933 (Sorkhabi, 2008). Philby was added to Socal’s payroll and secretly hired as an advisor to the company (Sorkhabi, 2008 & Yergin, 1991). Determined to get Ibn Saud the best deal, Philby contacted the APOC and IPC to place bids for the concession (Sorkhabi. 2008 & Yergin, 1991). The British, represented by Stephen Hemsley Longrigg could only offer £6,000 –– no match for the Americans’ offer (Sorkhabi, 2008). After a series of long negotiations, the final agreement amounted to £35,000 in gold upfront, a second loan of £20,000 after 18 months, an annual rental fee of £5,000 (with the first year paid upfront), and a royalty of 4 shillings per ton of oil produced (Sorkhabi, 2008 & Yergin, 1991). The official concession was signed on May 29, 1933 and would be valid for 60 years (Sorkhabi, 2008).

Operations in the country were founded by California Arabian Standard Oil Company (CASOC) in the autumn of 1933 as a subsidiary of Socal (Sorkhabi, 2008). Geologists R.P. “Bert” Miller, S.B. “Krug” Henry, J.W. “Soak” Hoover, Thomas Koch, Art Brown and Hugh Burchfield were sent to the country to explore for oil. Their expeditions would discover the Dammam Dome, an anticline structure the locals called Jabal (“Hill”) Dhahran (Sorkhabi, 2008). Socal sent an airplane in the spring of 1934, piloted by geologist, Dick Kerr, to map the area (Sorkhabi, 2008).

The first six Dammam wells did not strike oil successfully. It was Dammam No. 7 that struck oil in commercial quantity on March 5, 1938 (Sorkhabi, 2008). A 63km pipeline was formed from the Dammam field to the port of Ras Tanura in 1939, where a refinery was built (Brown, 1999 & Sorkhabi, 2008). King Ibn Saud visited Ras Tanura on May 1, 1939 to observe the first oil cargo from Ras Tanura transported by a Socal tanker called D.G. Scofield (Sorkhabi, 2008). On May 31, 1939 the oil concession was expanded to grow from 830 thousand to 1.14 million square km of coverage (Sorkhabi, 2008).

The ownership of Aramco also shifted over time. In 1936, Texaco bought 50% interest in CASOC and in 1948 Standard Oil of New Jersey and Socony-Vacuum (both now ExxonMobil) bought interests in the newly named (in 1944) Aramco (American Arabian Oil Company) (Sorkhabi, 2008). Nationalization efforts began in the 1970s with Saudi Arabia purchasing 25% of Aramco’s assets in 1973, then 60% in 1976 before wholly owning the company in 1980 and renaming it to the company we know today as Saudi Arabian Oil Company or Saudi Aramco (Brown, 1999 & Sorkhabi, 2008).

Today, Saudi Aramco’s standing in the industry spans beyond the region and has become a company to be reckoned with internationally. The involvement of America in the country would be the start of a new era of geopolitics and oil-based economies in the region.

Kuwait

Kuwait is one of the earliest established states in the Gulf region and was a major strategic hub between the British strongholds in India and Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq).

The then Amir of Kuwait Sheikh Ahmad Al-Sabah was approached by the Gulf Oil, represented by Holmes’ company, and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) about finding oil in his kingdom (Yergin, 1991). While Gulf Oil was keener to explore, the APOC was skeptical about oil prospects in Kuwait APOC executives in Iran –– the location of their most valuable concession –– were worried about how pursuing a concession in Kuwait would look like to the Iranian Shah (Yergin, 1991). APOC, however, could not just sit and allow another company to potentially undermine its position and influence in Persia and Iraq, and decided to pursue an oil concession in Kuwait (Yergin, 1991).

There were two main economic considerations in the granting of an oil concession in Kuwait. First, the local pearling trade had recently sunk because of the introduction of locally cultured pearls by a Japanese noodle vendor, Kokichi Mikimoto. Second, the Great Depression reverberated outside the US and crippled the economies of the Gulf region. A geopolitical reason was also factored in. Sheikh Ahmad was upset at Britain for what he thought was inadequate support in various controversies Kuwait had with Saudi Arabia and Iraq. Sheikh Ahmad believed that the entry of an American oil company would bring along with them American political interest, which he thought would bolster his position against Britain and his regional rivals (Yergin, 1991).

Sheikh Ahmad knew that he still needed Britain’s military protection and the British government wanted to do everything it could to maintain its influence and position in the region –– and in this case it means ensuring that the oil concession went to a British company. This was supported by the British Nationality Clause, which barred any foreign company from operating in the region and exclusively restricted oil development only to a British-controlled firm, which was strongly contested by the Americans. After much thought, the Foreign Office, the Colonial Office and the Petroleum Department of the British government were all prepared to drop the Nationality Clause in April 1932. Britain was aware of the political and economic benefits of allowing America to enter the region and lost the battle in trying to fend them off (Yergin, 1991).

Moreover, the APOC chairman, Sir John Cadman, had told the Foreign Office that “any oil found in Kuwait would not be of interest to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company,” and that “the Americans are welcome to what they can find there” (Yergin, 1991, p. 294). Cadman would soon highly regret what he had just told his government. In May 1932, Socal made its first oil discovery in Bahrain, which immediately changed the situation and perspective of the British government. Cadman rushed to write to the Foreign Office to rescind his statement of no interest in Kuwait, and suddenly APOC was now back in the bidding war. Sheikh Ahmad was pleased at the news that two bidders were back on the table as “from the point of view of a seller that is all to the good” (Yergin, 1991).

Cadman had attempted to negotiate an all-British development in Kuwait with Sheikh Ahmad while on his way to Persia in March 1933, but he was a few hours too late. By the time the APOC chairman arrived, Major Holmes had already been given the promise to allow Gulf Oil to top whatever offer Cadman might put on the table (Yergin, 1991).

Defeated and upset, Cadman knew that the only way forward was to establish a joint venture with Gulf Oil. After series of tough negotiations between the two companies (Gulf Oil and APOC), a new fifty-fifty joint venture and thus a new company was created: the Kuwait Oil Company (Yergin, 1991). However, discussions did not end there. The British Foreign Office, fearful of American companies’ expansionist power, insisted that all operations on the ground were “in British hands,” thus resulting in a new agreement that was finalized in March 1934 to guarantee just that (Yergin, 1991).

After strenuous negotiations, an agreement with Sheikh Ahmad was reached on December 23, 1934. Sheikh Ahmad granted a 75-year concession to the Kuwait Oil Company. In return, he would receive an upfront payment of US$179,000 and until oil was found in commercial quantities, he would receive annual payments of US$36,000 at minimum (Yergin, 1991). Once oil was found, payments would be increased to an annual minimum of US$94,000 and could be higher depending on the volume of oil found (Yergin, 1991). Sheikh Ahmad also appointed Major Frank Holmes, his old friend, as his representative to the Kuwait Oil Company in London, a position he held until his death in 1947 (Yergin, 1991).

The United Arab Emirates

The UAE of today is often described as opulent and developed, with mental-imagery of extravagant buildings, modern infrastructure and riches-galore –– though this was not always the case. In the 1930s, the country mainly depended on fishing and pearling –– a common source of income for most nations in the region.

Following Britain’s declaration to end its protection of the Gulf States in 1971, the rulers of Abu Dhabi and Dubai worked to create a federation that would consist of the seven emirates of the Trucial States, Qatar, and Bahrain. But Qatar and Bahrain decided not to join. On December 2, 1971, six emirates formed United Arab Emirates. The seventh emirate Ras Al Khaimah joined in 1972 (Euronews, 2018). Abu Dhabi was selected as the administrative capital of the nation. It would also became the oil capital of the country. Today, the nation is thought to possess the sixth largest proven oil reserves in the world (Morton, 2011).

In the early 1930s, the then-ruler of UAE, Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan al Nahyan was eager to find a good water supply after hearing about Major Frank Holmes’ discovery of water in Bahrain (Morton, 2011). After a suggestion from Holmes, a request was made to the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) whose partners included the Anglo Persian Oil Company (APOC). In 1935, APOC geologist Peter Cox arrived to find the sheikh was now more interested in oil rather than water because of what he had heard about other rulers' financial gains from the natural resource. A two-year concession was made on January 5, 1936, to William “Haji” Williamson on behalf of the IPC and a subsidiary was made under the name Petroleum Development (Trucial Coast) (PDTC) to explore the area (Morton, 2011).

The exploration would later turn out to be quite unsuccessful because of the limitations that the technology available at the time presented. It would not be until around a decade later that a new technology (seismic reflection) would be available. Unshaken by the difficulties, PDTC obtained a 75-year concession for the whole territory on January 11, 1939 (Morton, 2011).

Due to World War II, exploration had to be put on hold until 1946 when gravity surveys were eventually conducted. The terrain proved to be too difficult for the land vehicles to navigate, so after a break of three years, surveys would resume with special equipment and helicopters (Morton, 2011). Land transport, technology and equipment improved, and so substantial progress could finally be made.

Drilling finally began in 1950 and 1951 when PDTC drilled for oil at Ras Sadr and Jebel Ali respectively. But no oil was found. Further issues arose when a border dispute with Saudi Arabia, known as the Buraimi Affair, would close parts of Abu Dhabi to oil exploration. The Buraimi Affair included a series of negotiations and battles that took place to influence the loyalties of tribes in and around the Buraimi oasis whose tribal areas were split in the Trucial States when the oil companies came to seek concessions (Morton, 2015). Other wells were drilled in the Trucial States but all came back dry.

More oil would be found offshore, however. The Abu Dhabi Marine Areas (ADMA), a company jointly owned by British Petroleum and Compagnie Française des Pétroles (later known as Total), had obtained an offshore concession. Jacques Cousteau was sent by the company with his research ship, Calypso, to map the sea bed. Following this mapping, a seismic survey was conducted by GSI Ltd. using their ship, mv Sonic, which located the site for the first test well. In 1958, the ADMA Enterprise, a marine drilling platform, commenced operations and oil was struck at about 8,755 ft (2,668m) on the Umm Shaif field. The field would turn out to be a supergiant about 300km² in size. PDTC’s onshore well at the Murban-bab oilfield struck oil in 1959. PTDC made additional discoveries in 1962 in the Bu Hasa oilfield and ADMA discovered the Zakum offshore oilfield in 1965 (Morton, 2011).

In the early 1960s PDTC relinquished a lot of the Trucial Coast area from its concession –– possibly due to the beginnings of Britain’s decision to withdraw much of its influence and control in the region, but retained Abu Dhabi. It then later changed its name to Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company (ADPC) (Morton, 2011). A 50-50 oil sharing agreement was signed with Sheikh Shakhbut in 1965 and ADMA would later agree to the same terms in 1966. In 1971, after Sheikh Zayed, Shakhbut’s brother, became president of the newly created UAE, the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (present day ADNOC) was created. The national stakes were raised to 60% in December 1974 and ADPC and ADMA would be reincorporated as the Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operation and Abu Dhabi Marine Operating Companies (Morton, 2011). Nationalization efforts were a common trend you will find across the region. Today, as with most of the Gulf states, oil and gas from Abu Dhabi and Dubai have become the predominant source of income for the wider UAE, developing it into the wealthy nation we know today.

Oman

The history of discovery in Oman is complex. The first recorded history of the search for oil in Oman was in 1904, when the Government of India (then a part of the wider British Empire) dispatched Guy Pilgrim to examine the Gulf (including Oman) but he returned with a report that time would be better spent in Persia (Morton, 2012).

It was not until the 1920s when oil activity restarted in Oman. Frank Holmes’ activities in the region prompted the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) to explore Oman through its exploration arm, D’Arcy Exploration, which had obtained a two-year license to prospect Oman in 1925. The exploration was not productive as they had hoped because of the unrest present in the region at the time (Morton, 2012).

Another attempt was made by the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) in 1937 through the concessions they obtained for Oman and Dhofar but this too turned out to be unsuccessful. The then ruler, Sultan Said bin Taimur, gave his blessings to explore Buraimi. But a leading sheikh in the area used the opportunity to ambush the company geologists because he thought the moment was “a God-given opportunity for a ‘first class hold-up’.” (Morton, 2012, p. 71). The geologists escaped unharmed, but it ended their exploration efforts for the time being

In 1939, an aerial reconnaissance was conducted but nothing of interest was found. The success of Aramco in the region reignited interests for the IPC and after a report of “potentialities of oil in Dhofar'' by Sir Cyril Fox (formerly of the Geological Survey of India), exploration was resumed again in February of 1948 (Morton, 2012, p. 72). This however, turned out to be fruitless again and in December 1950, the company relinquished its concession.

Wendell Philips, an American archaeologist with little knowledge of the oil business was granted a concession by the Sultan in 1952 for the region of Dhofar. Philips assigned this concession to the American oil company, Dhofar-Cities Service Petroleum Corporation. While exploration from 1955 until 1958 seemed to be encouraging at first, the oil from Marmul was too heavy to exploit commercially. To add to the difficulty, oil prices were low at the time and the monsoon season hampered logistical support around the coast. In 1967, the company was forced to relinquish the concession after an expenditure of $40 to $50 million and 29 wells sunk (Morton, 2012).

The IPC did not make much progress. In1952 the operating company dropped Dhofar from its title to become Petroleum Development Oman (PDO). Due to the unrest in Buraimi because of internal conflict and Saudi occupation, the company decided to approach Jebel Fahud –– the main source of interest –– from the south via Duqm Bay (Morton, 2012). After exploration wells were drilled in Ara, Ghaba, Haima and Afar between 1956-1960 there was still no indication of oil in commercial quantities (Morton, 2012). The global supply of crude oil was still exceeding demand, causing prices to be low. Political instability was also still a huge issue in the region. This forced three of the IPC partners to withdraw, leaving Shell with 85% and Partex with 15% as partners in the PDO.

It was not until Shell took over and led the way that substantial progress was made. After a new drilling program started in 1962 following the discoveries made in Abu Dhabi, oil and gas was found in the Yibal oilfield 48km south-west of Fahud (Morton, 2012). The areas surrounding Jebel Fahud proved to be productive from 1962 onwards and the export of Omani oil finally began on 27 July 1967 (Morton, 1967). The Omani government acquired a 60% stake in PDO in 1974 and remained to be the majority shareholder to this day (pdo.co.om).

Qatar

Qatar’s oil history and development

Qatar, a small peninsular nation, has wealth and influence far greater than its size may suggest. Before becoming a British protectorate in 1916, Qatar was ruled under the Ottoman Empire from 1872 to 1914.

The search for oil in Qatar did not start until the 1920s. In 1923, Major Frank Holmes met with Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani, Qatar’s ruler at the time, to discuss the option of oil exploration in the country (Sorkhabi, 2010). Holmes’ intentions were thwarted by the British Colonial Office, with whom he dealt with through the British political resident in the Gulf, Sir Percy Cox, who barred all oil ventures in the nation (Al-Othman, 1984 & Sorkhabi, 2010).

In the same year (1923), the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) submitted a similar request to the Qatari ruler for permission to obtain a concession but was also rejected by the British political resident (Al-Othman, 1984). This rejection from the British political resident was highly suspicious as APOC operated in the British Government’s best interests and was backed by His Majesty’s Government themselves (Yergin, 1991).

The British Government was playing the long game. In order for them to not show outright favor, they rejected APOC’s initial request and ensured that no oil-related activities would occur in the country for the next two years. Once initial suspicions subsided, APOC submitted their request to the British political resident in the Gulf in 1925 for permission to conduct a preliminary geological survey in Qatar (Al-Othman, 1984). This request would be happily granted by the British Minister of State for Colonial Affairs on December 14, 1925 (Al-Othman, 1984, p. 18).

The British Government’s motives would become apparent later. They wanted to do all they could to keep the Eastern and General Syndicate who represented American interests out of Qatar while trying their best to not show favor to a particular company (Al-Othman, 1984). This would be further proved when APOC would send a geological team to Qatar in 1926, which also managed to secure an agreement for no further exploration concessions to be made for the next 18 months (Al-Othman, 1984).

APOC would make no real effort to search for oil for the next few years. It was not until 1932 when they realized the competition and potential consequences of putting Qatar’s oil aside would their behavior change. A representative of the Eastern General Syndicate, Hussein Yateem, was sent to Qatar on June 11, 1932 to try to obtain a concession (Al-Othman, 1984). Informed of America’s growing foothold and power in the Middle East through their operations in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia (all with the help of the Syndicate), the British Government immediately informed the APOC to make their move (Al-Othman, 1984).

In sharp contrast to their lack of tangible interest in the last seven years, the company sent C. C. Mylles and Arabic-speaking English Muslim, Hajji Abdullah Williamson on August 20, 1932 to negotiate terms with Sheikh Abdullah (Al-Othman, 1984). A new contract was signed on August 25, 1932 that renewed the terms of the 1926 APOC agreement, included a two-year survey period and most importantly gave APOC (or any company of their choice) first pick to any subsequent concession (Al-Othman, 1984). The agreement also prohibited Sheikh Abdullah from offering any oil-related concessions to other companies trying to operate in the country (Al-Othman, 1984). In return, the Sheikh would be paid 1,000 Indian Rupees (Rs) a month (Al-Othman, 1984). The British political resident in the Gulf soon ratified the agreement on the British Government’s behalf and in accordance with the Treaty of Protection (which made Qatar a British Protectorate) signed in 1916 that gave Britain exclusive rights to veto any business dealings in the country (Al-Othman, 1984).

The Eastern and General Syndicate attempted to investigate what had happened in Qatar but was immediately shut down. The Americans, who the Eastern and General Syndicate practically represented, demanded to know why the British Government imposed the total monopoly and barred them from participating in Qatar (Al-Othman, 1984). Britain’s official response included: “to concentrate all Qatar's oil concessions in the hands of British companies to save Britain the trouble of ‘reviewing the organization of postal services, as well as British supervision and protection of foreign subjects’” (Al-Othman, 1984). This would be the start of a precarious relationship between Britain (and all its representatives –– individuals and corporations) and Qatar’s ruler to balance their interests with keeping the Sheikh satisfied and unsuspicious. This relationship would include British attempts to strong-arm Qatar’s ruler by reminding him of the agreements made in the 1916 Treaty of Protection and Britain’s influence over the work done by the APOC in the country (Al-Othman, 1984).

However, Britain’s monopoly in Qatar posed a massive problem for APOC. The company signed the Red Line Agreement in 1928 with the consortium of oil companies known as the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) (Yergin, 1991). In effect, the company, being a member of the consortium, could not operate in any oil-related activities within the former Ottoman Empire of the Middle East –– which included Qatar (Sorkhabi, 2010).

After visits from IPC representatives and much negotiations between IPC officials, APOC and the Qatari ruler, a new agreement was made: APOC would act as IPC’s nominee in Qatar (Al-Othman, 1984 & Sorkhabi, 2010).

In late 1932, APOC sent two geologists, E.W. Shaw and P.T. Cox to Qatar and after a survey between January to March 1933, the team discovered that the geology of Dukhan (an area on the western coast) was similar to the oil field discovered in Bahrain (Sorkhabi, 2010). All this work could not have been done or even started without the invaluable guidance from Sheikh Mansour Al-Hajri, a Qatari who had incredible knowledge of Qatar’s landscapes (Al-Othman, 1984).

In 1933-1994, APOC employees W.E. Browne and D.C. Ion began to precisely map the Dukhan area (Sorkhabi, 2010). After successfully mapping the area, APOC began negotiations with Qatar who eventually granted them a 75-year oil concession covering all of Qatar’s land on May 17, 1935 (Sorkhabi, 2010). The negotiations were tough, with the British officials trying to exploit the oil at the cheapest expense possible and the Qatari government aware of the wealth that could be reaped from riches beneath their sand (Al-Othman, 1984). After multiple back-and-forth discussions, a promise of British protection, British influence over the appointment of Qatar’s Heir Apparent and overall mounting pressure from the British government, a decision was finally made (Al-Othman, 1984). The Qatari government would be given two Indian rupees per ton of oil produced, an initial payment of Rs. 400,000 and an annual sum of Rs. 150,000 for the first five years before increasing to Rs. 300,000 annually (Al-Othman, 1984 & Sorkhabi, 2010).

The year 1937 marked the creation of the Petroleum Department of Qatar, formed by APOC on behalf of IPC. The company’s shareholders included: APOC (23.75%, later transferred to British Petroleum), Royal Dutch Shell (23.75%), Cie Francaise des Petroles (23.75%), Standard Oil of New Jersey (11.87%), Mobil (11.87%) and Paratex (part of the Glubenkian Foundation, 5%) (Sorkhabi, 2010).

With the expert guidance of Al-Hajri in 1937-1938, Norval E. Baker, T.F. Williamson and R. Pomeyrol (a new group of geologists) were able to recommend a location in Dukhan for the very first exploratory oil well in the country –– Dukhan No. 1 (Al-Othman, 1984 & Sorkhabi, 2010).

Drilling for the well began in October 1938 and the well finally hit oil in the last weeks of 1939 (Sorkhabi, 2010). The well was completed in January 1940 and produced about 4,480 barrels of oil per day (Sorkhabi, 2010). Drilling operations expanded when Dukhan No. 2 was drilled around 16km south of the first well in March 1941, and Dukhan No. 3 around five-km east of the first well in May 1942 (Sorkhabi, 2010).

With the advent of World War II (1939-1945), operations in Dukhan were halted on June 28, 1942, with wells and installations either stripped or destroyed (Al-Othman, 1984 & Sorkhabi, 2010). The company left protection of their equipment and property to around a dozen men headed by Al-Hajri because of their confidence in his abilities and loyalty (Al-Othman, 1984). The five years when operations were at a standstill were difficult for the population of Qatar. While money was still being sent to Qatar, the company’s former workers were forced to find work elsewhere –– with some travelling to neighboring countries in hope of a job at one of the other oil companies (Al-Othman, 1984).

Operations resumed in late 1947 and the company used three drilling rigs to drill a total of 25 wells. It also constructed a 120km pipeline from Dukhan to the port of Umm Said in eastern Qatar (Sorkhabi, 2010). On December 31, 1949, the SS President Manny left the port of Umm Said carrying the country’s first oil export –– 80,000 tons worth of it –– headed to Europe (Al-Othman, 1984 & Sorkhabi, 2010).

In August 1949, Sheikh Ali bin Abdullah Al-Thani, Qatar’s new ruler and the former Emir’s oldest son, granted an offshore oil concession to International Marine Oil Company (a subsidiary of American company, Superior Oil Company and Investment Corporation) (Sorkhabi, 2010). The Qatar Petroleum Company (QPC) protested the offshore concession for supposedly infringing the terms of the original concession agreement (Al-Othman, 1984). Tribunal meetings held during Sheikh Ali bin Abdullah Al-Thani’s reign concluded in November 1950 that “the concession granted to Petroleum Development (Qatar) Ltd does not include the sea bed or what lies beneath it, nor any part of the floor of the Gulf adjacent to the coastal waters,” and therefore the concession stood (Al-Othman, 1984). However, International Marine could not locate any suitable structure for drilling and were forced to give up their concession in 1952 (Sorkhabi, 2010).

Qatar granted a new offshore concession to Shell Overseas Exploration Company and eventually transferred it to a new subsidiary called Shell Company of Qatar in 1954. The 75-year concession covered a 25,900 square-km area and included an initial payment of £260,000 along with a 50-50 profit sharing after production. Under the same agreement, operations were bound to begin within nine months and drilling to be commenced within two years (Sorkhabi, 2010).

As narrated by historian Rassoul Sorkhabi, seismic surveys were conducted by Shell in spring 1953 before exploratory wells were drilled in 1955 and 1956 –– though both wells came back dry. The tides turned in May 1960 when Shell discovered the Idd al-Sharqi oil and gas field 85km east of Doha –– consisting of the larger North Dome (which was discovered and produced first) and the smaller South Dome. Another major offshore field was found in 1963 by Shell, called the Maydan Mahzam field, which started production in 1965. By 1969, Qatar’s earnings amassed to $115 million consisting of a total oil production of 17 million tons (293,000 barrels of oil). The first shipment of oil produced from the Idd Al-Sharqi North Dome field was exported from the island of Halul (located 80km northeast of Doha, housing pumping stations and loading terminals for tankers) on February 1, 1974 (Sorkhabi, 2010).

Nationalization of the Qatar Petroleum Company

While initially starting out as a totally foreign-owned and operated oil company, Qatar Petroleum Company was envisioned by the Qatari government as being their own national company one day. The formal process of this began in the 1970s. On January 10, 1973, Sheikh Abdulaziz bin Khalifa Al-Thani, Qatar’s Minister of Finance and Petroleum signed the first participation agreement with Qatar Petroleum Company (QPC). The agreement granted Qatar 25 percent participation in QPC’s concession with further 5 percent increments being given each year until a total 51 holding would be reached in 1983. This agreement was the first to be finalized in the Gulf under the newly found terms of the OPEC General Participation Agreement that began the process of stripping control from foreign companies and allowing local governments to hold influence over their oil resources (Al-Othman, 1984). A second participation agreement was signed on February 20, 1974 which granted Qatar a 60 percent holding. This agreement would give Qatar 60 percent ownership of all operations, oil rights and facilities (including those for gas liquefaction) (Al-Othman, 1984). This agreement guaranteed and further established Qatari control and influence of their oil wealth.

A similar agreement to the first one with QPC was signed on January 5, 1973 with the Shell Company carrying the exact same terms: 25 percent ownership was to be granted to Qatar with an additional five percent being given each year until 51 percent was reached in 1983. This agreement was changed again in 1974 to match the second QPC deal, which granted Qatar 60 percent participation in all offshore operations and profits (Al-Othman, 1984).

On December 22, 1973, Sheikh Abdulaziz, put out an official government statement outlining Qatar’s intention to acquire the remaining 40 percent of shares in both companies. A Ministerial Council decree (Decree no. 1 of 1975) was then announced on February 8, 1975, declaring Qatari ownership of those shares. Agreements were finally made with Qatar Petroleum Company on September 16, 1976 and with Shell Company of Qatar on February 9, 1977; and officially ratified in Law no. 100 of 1976 (for QPC) dated October 11, 1976 and Law no. 10 of 1977 (for Shell Company of Qatar) dated March 2, 1977 (Al-Othman, 1984). Thus, all oil and gas wealth now officially belonged to the State of Qatar. This was a new chapter for the nation and one that launched Qatar on track to the nation we know it as today.

A series of subsidiaries were created under the Qatar General Petroleum Company (the successor to the Qatar Petroleum Company, and predecessor to Qatar Petroleum, recently changed again to Qatar Energy) to expand its reach across downstream industries. National Distribution Company (of which its assets were transferred to the company we know today as WOQOD), Qatar Petrochemicals Company (QAPCO), Qatar Fertiliser Company (QAFCO) and Qatar Gas Company were among the companies created (Al-Othman, 1984).

Over the next few decades, Qatar and its oil and gas industry would see massive growth and development. Joint ventures between huge multinational corporations like ExxonMobil, Total and Shell would be created and developed all the while maintaining a majority national control. Today, with the massive gas reserves the nation possesses, Qatar’s focus has shifted to natural gas and has renamed Qatar Petroleum to Qatar Energy as a signpost in its diversification objectives.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF): Qatar’s perspective

Qatar had been a prominent member of OPEC from its creation. Qatar attended the founding meeting of OPEC in September 1960 as an observer and officially joined the organization the following year, a membership they held until their self-decided termination on January 1, 2019 –– a move made to signal their intent to focus on natural gas (Colgan, 2018).

The origins of GECF can be traced to May 19, 2001, when Qatar –– along with Algeria, Brunei, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Oman, Russia, Turkmenistan and Norway as an observer –– formed the group during a ministerial meeting held in Tehran, Iran (GECF, n.d.). This was the start of a series of meetings that eventually established the full-fledged international organization in 2007 in Doha, Qatar, before the first official summit was held in Doha on December 15, 2011 (GECF, n.d.). Similar to OPEC, GECF was made to be an international organization for coordination and collaboration as well as to “support the sovereign rights of its members over their natural gas resources and their abilities to develop, preserve, and use such resources for the benefit of their peoples'' (GECF, n.d.). While shocking to the rest of the world, the late 2018 announcement (that signaled Qatar’s official termination in 2019), was made to solidify Qatar’s commitment to GECF and their main focus in the gas industry.

Labor history of the oil and gas industry in Qatar

The success and wealth the State of Qatar has garnered over nearly the last century would not have been possible without the early pioneers of the oil and gas industry in the country. The manual and semi-skilled workforce of the Qatari men in the 1930s played a key role in establishing the oil and gas industry in the nation. These men were subject to hard labor, dangerous working conditions, segregation between employees, strict routines, limited mobility, extreme discipline, and meager compensations.

The Qatari men at the time were subject to long hours –– working day and night –– doing manual labor jobs like carrying heavy materials (in their jobs as “coolies”), doing the dirty work in the rigs and any other odd-job that the British needed done (Al-Othman, 1984). Danger was always close in their jobs working for the oil company. One incident that occurred was the collapse of a rig structure –– Rig no. 2. Three men of the men involved: Jassem bin Qroun Ibrahim al-Dosari, Abdulrahman bin Nasser and Massoud Bulkmout were standing on the top level of the rig, lowering drilling pipes when suddenly the platform they were all standing on collapsed, causing them to all fall (Al-Othman, 1984). They all suffered injuries, with Abdulrahman breaking his wrist while Jassem bin Qroun “landed on his hip and suffered urinary and vascular congestion” (Al-Othman, 1984, p. 87). These men had to be transported to Bahrain to receive medical treatment –– a testament to the scarcity of available care in the country at the time –– and eventually recovered. However, to this day, both Abdulrahman and Jassem bin Qroun suffer from back pain (Al-Othman, 1984).

Another aspect of the working conditions of the early Qatari oil workers was segregation, which was very apparent between the British and Qatari employees. British employees that lived around Dukhan at the time had proper houses to live in, while Qatari employees were subject to living in “barracks, made of mud and stones” (Al-Othman, 1984, p. 51). While the company did provide entertainment that the Qatari workers had access to, like a cinema that played silent films, infrastructure like tennis courts were only allowed to be accessed by the British employees (Al-Othman, 1984).

These men were also subject to strict routines and limited mobility –– all enforced with strict disciplinary actions. Initially, Qatari employees were only allowed to go to Doha, from their work in Dukhan, once a month where they would stay less than a day before returning back to the desert (Al-Othman, 1984). Conditions did improve over time when they were able to go home every fortnight. Weekly leave was finally introduced in 1950 where they were able to stay in Doha from Thursday afternoon to Friday morning (Al-Othman, 1984). Employees who fell asleep on the job –– a reality difficult to avoid with the long hours they were forced to work –– were given two warnings before being fired. Bu Abbas, one of the pioneers in the oil industry and the first Qatari driver to be employed by the company, recalls that “there was one terrible man called Henderson who was very hard on us and was always looking for some excuse to punish us” (Al-Othman, 1984, p. 80).

To add to the harshness, these men were not paid very well. Their pay varied from a mere ¾ rupees to 4 rupees a day in the beginning, before strikes and demands finally improved their wages (Al-Othman, 1984). Additionally, overtime pay was not a concept employed by their British supervisors while these Qatari men were subject to working day and night (Al-Othman, 1984). Often understated or unmentioned entirely by Western scholars, the sacrifices of these men would prove vital and priceless to the creation and growth of the oil and gas industry in Qatar we know in the present.

Today, the technologies and processes involved in the oil and gas industry have come a long way, thus making occupational hazards a far lesser danger. While occupational hazards have decreased, shortcomings in the treatment of oil and gas workers still exist today. Unfair treatment, exploitation, and segregation of foreign workers; and inadequate facilities and equipment suitable for women are still a reality to some in the nation and region.

Summary

The oil and gas industry has a rich history in the Gulf. The start of the industry’s history in the region can be traced back to Persia (modern-day Iran) where oil was first found at the start of the 20th Century. The British, represented by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (the precursor of modern-day BP would become one of the leaders of the discovery and exploitation of oil in not only Persia but also the region. Arguably equally as important was the involvement of Iraq in the region’s oil industry, the first country where the United States would enter and establish a stake in the oil-rich region. This trend of Anglo-American involvement (through exploration and exploitation of oil) would continue on in countries such as: Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, Oman, and Qatar. Each of these countries, after decades of majority-control by these Western powers would seek nationalization and ownership of oil companies and production through Western withdrawal from the region, local investment and the creation of an influential cartel involving some of these countries (among others) we know today as OPEC (The Organization of the Petroluem Exporting Countries).

A particular focus is placed on the small peninsular nation of Qatar, where its wealth and influence are disproportionate from what its minute size may suggest. Its oil and gas industry roots are similar to its neighbors with the involvement of predominantly British influence before finally nationalizing its production and ownership of the resources. To counter the leeching influence of OPEC, Qatar –– among other nations –– spearheaded the creation of GECF (the Gas Exporting Countries forum). Gas is now Qatar’s main focus, especially after the nation’s departure from OPEC. The oil, and more particularly, gas industry in Qatar is alive and well and continues to display steady growth as the country diversifies its energy industry and develops it with the help of massive local investment and international expertise.

All of this would not have been possible without the men and women behind the industry’s grueling labor history. Once subject to intense and brutal manual labor, Qatari men would literally develop and grow the industry out of literal dust to become what it is today. These men were subject to ill-treatment from their British counterparts and managers –– a reality that would only change once the process of nationalization of the industry took place in 1975. Today, Qatari men now comprise a minority of the industry’s workforce, replaced by foreign workers (men and women) from all over the world. The realities of a crucial part of today’s workforce and their lived experiences are explored in our next module, Module 3, where challenges for female professionals in the industry are explored as well as a look into the hopes and aspirations they have for the future.

Sources

Al-Othman, Nasser. (1984). With their Bare Hands: The Story of the Oil Industry in Qatar. Longman House. Essex, England.

Archer, Sinead. (2012, September). Bahrain: 80 years and Still Producing. GeoExpro. URL: https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2012/12/bahrain-80-years-and-still-producing

Brown, Anthony C.. (1999). Oil, God, and Gold: The story of Aramco and the Saudi Kings. Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, NY, United States of America.

Colgan, Jeff D. (2018, December 6). Qatar will leave OPEC. Here’s what this means. The Washington Post. URL: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/12/06/qatar-will-leave-opec-heres-what-this-means/

Euronews. (2018, December 7). How was the UAE founded? URL: https://www.euronews.com/2018/12/07/how-was-the-uae-founded

Gas Exporting Countries Forum. (n.d.). GECF History. URL: https://www.gecf.org/about/history.aspx

Hobbs, Mark. (n.d.). Oil maps of the Middle East. British Library. URL: https://www.bl.uk/maps/articles/oil-maps-of-the-middle-east

Morton, Michael Quentin. (2012, June). Once Upon a Red Line - the Iraq Petroleum Company Story. GeoExpro. URL: https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2013/06/once-upon-a-red-line-the-iraq-petroleum-company-story

Morton, Michael Quentin. (2011). The Abu Dhabi Oil Discoveries. GeoExpro. URL: https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2011/03/the-abu-dhabi-oil-discoveries

Morton, Michael Quentin. (2012). The Search for Oil in Oman. GeoExpro. URL: https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2012/06/the-search-for-oil-in-oman

Sorkhabi, Rasoul. (2009). Oil from Babylon to Iraq. GeoExpro. URL: https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2009/02/oil-from-babylon-to-iraq

Sorkhabi, Rasoul. (2008). The Emergency of the Arabian Oil Industry. GeoExpro. URL: https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2008/06/the-emergence-of-the-arabian-oil-industry

Sorkhabi, Rasoul. (2010). The Qatar Oil Discoveries. URL: https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2010/01/the-qatar-oil-discoveries

Smil, Vaclav. (2008). Oil: A Beginner’s Guide. Oneworld Publications. Oxford, England.

U.S. Office of the Historian. (n.d.) The 1928 Red Line Agreement. Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, U.S. Department of State. URL: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/red-line

Yergin, Daniel. (1991). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. Simon & Schuster. New York, NY, United States of America.